Marine protection areas

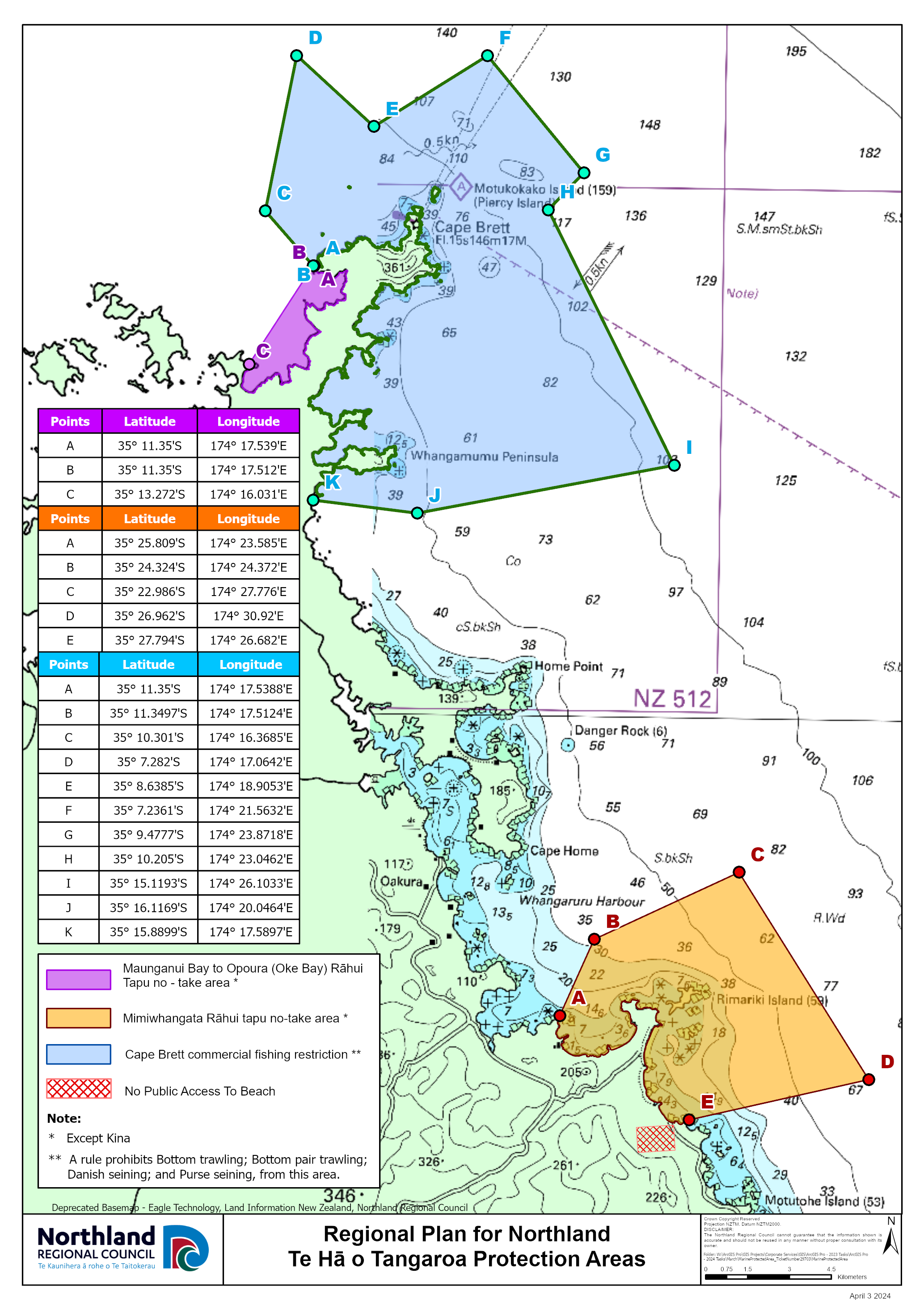

New rules are now in place for marine protection areas in Mimiwhangata and Rakaumangamanga (Cape Brett). This means you can no longer take marine life from the areas shown in the map below.

The new rules have been introduced to protect the significant ecological values of these areas, which have been severely impacted by fishing.

These rules do not affect kina harvest daily bag limits, or non-commercial Māori customary fishing rights guaranteed under Te Tiriti o Waitangi, but a permit is required – see below for more information.

There are two new no-take fishing areas:

- Maunganui Bay (Deep Water Cove) to Opourua (Oke Bay) in the Bay of Islands (Rakaumangamanga Rāhui Tapu)

- Around the Mimiwhangata peninsula (Mimiwhangata Rāhui Tapu).

In a third area, around Cape Brett, bulk harvesting of fish using specific commercial seining and trawling methods is prohibited to a depth of 100 metres (Ngā Au o Morunga Mai Rakaumangamanga Protection Area).

Boundary description: Mimiwhangata marine protected area

The Mimiwhangata southern boundary extends 6.2 kilometres offshore from Tauranga Kawau Point (just north of Titi Island), with the sea-ward boundary continuing north-west 8.7 kilometres past Rimariki Island. The northern boundary extends 2.9 kilometres north-north-east from Paparahi Point, and continues a further 5.7 kilometres north-east out to sea.

Boundary description: Rakaumangamanga marine protected area

The Rakaumangamanga rāhui tapu area begins from north of Opourua (Oke) Bay between Moturahurahu Island and Kohangaatara Point and travels approximately 4.3 kilometres north-east to Kariparipa Point, past Maunganui Bay and Putahataha Island.

NZTM Projected co-ordinates are provided in the table

Latitude and longitude co-ordinates are provided in the table

In May 2023 the Environment Court released its final decision on new marine protection rules for Mimiwhangata and Rakaumangamanga (Cape Brett).

The court decision directs Northland Regional Council to implement the new rules via our Regional Plan, as fishing was shown to have been causing significant disruption and deterioration to the ecosystems.

Fishing restrictions were not originally included in the Proposed Regional Plan when it was released for consultation in 2017 which led to the appeal to the Environment Court that council should have fishing protections in these areas.

In November 2022 the Court issued a judgment upholding the appeal. Court processes meant public consultation on the issue was not possible.

Council supported the court’s decision on the basis that the evidence showed significant ecological values in the three areas were negatively impacted by fishing, reflecting the concerns of local hapū Ngati Kuta ki Te Rawhiti and Te Uri O Hikihiki who wanted protections put in place.

The Regional Plan for Northland, including the new marine protection rules, became fully operative on 31 July 2023.

Fishing has led to impacts on local ecosystems in the three areas now under protection.

This includes the collapse of tipa/scallop populations, disappearance of kutai/green lipped mussel beds, significant reduction in hāpuku numbers over large areas and loss from shallow water areas and decline in the size and number of workups.

When an ecosystem’s top predators are removed or changed, it can completely upset the balance underneath (this is known as trophic cascade). With tāmure/snapper and kōura/crayfish populations dramatically decreased, areas of kina barren (devoid of seaweed and kelp) have grown, dramatically changing these ecosystems. Tāmure/snapper and kōura are the main predators of kina in Northland.

The urgency of the issue and the need to act quickly to prevent further loss of ecological values was made clear during the Environment Court hearing.

‘No take’ marine protected areas are considered the most efficient tool to restore ecosystems and fish populations to a more resilient state. The recovery of species such as tāmure/snapper and kōura generally occurs within 5-10 years. The recovery of ecosystems in their entirety in marine protected areas takes considerably longer.

Anyone caught breaching the rules is committing an offence and liable for an infringement fine of up to $500, and ultimately prosecution with maximum penalties of imprisonment for up to two years or a fine up to $300,000 for an individual.

In short, we just need to give these areas a break to let nature restore its normal balance.

Customary fishing, or ‘customary rights’, is provided for under Article two of the Te Tiriti o Waitangi and gives Māori full, exclusive and undisturbed possession of all fisheries.

Māori customary fishing rights are recognised in law in both the Fisheries Act 1996 and Resource Management Act 1991.

Anyone can fish using customary rights but to do so you must be issued with a permit by a local kaitiaki who is an authorised customary fisheries permit issuer for that area. Permits must be issued before fishing commences and kaitiaki can only issue permits for areas in their specific jurisdiction. So, you need to have the right permit for the right area from the right kaitiaki.

Kaitiaki are appointed by their own iwi and hapū groups and confirmed by the Minister of Fisheries. Anyone wanting to fish under a customary permit need simply ask the local kaitiaki. It’s up to the person wanting to fish to know how to go about doing this. It is at the sole discretion of kaitiaki to issue a permit for customary fishing and describe what can be collected, why and when. More information can be found on the MPI website at: www.mpi.govt.nz/fishing-aquaculture/maori-customary-fishing/managing-customary-fisheries

Customary fishing compliance is managed by MPI fisheries officers who have the power to check the validity of customary rights permits. If permits are found to be false, or breached in terms of what it was originally issued for, the fisher can be prosecuted.

Monitoring and measuring the changes in these special marine areas will determine if the protections put in place by the court are achieving the desired biodiversity outcomes. That is, are the marine protection areas working?

How the monitoring will be carried out, and by who, is still being worked out.

It is intended that an interim working group will be established to implement the new rules and seek the advice of iwi, hapū and communities who are already involved in monitoring these areas and who will likely play a key role in their ecological recovery.