Mangroves

The mangrove tree is one of the marvels of our Northland harbours.

Forests of the harbour

It has adapted to living in the harshest of conditions - a dunking in salt water twice a day when the tide comes in and heavy, stinky mud with no oxygen for its roots.

There are not many other flowering trees that could survive in these conditions, yet the mangrove has adapted so well that it has formed dense forests in sheltered harbours in Northland.

However, it is now known that mangroves play an important part in the ecosystems of our harbours - sheltering young fish, stabilising land and forming a buffer zone to absorb floodwaters.

Hokianga mangrove forest.

Hokianga mangrove forest.

Council's policy on mangroves

Extensive areas of mangrove forest and saltmarsh in harbours on both coasts provide a haven for young fish species and feeding and roosting areas for coastal birds. Sustaining a beautiful coastline for future generations takes planning. The council's Proposed Regional Plan sets out rules and guidelines for the region's "coastal marine area", which is the area from mean high water springs to the 12 nautical mile (22.2km) limit of New Zealand's territorial sea.

Extensive areas of mangrove forest and saltmarsh in harbours on both coasts provide a haven for young fish species and feeding and roosting areas for coastal birds. Sustaining a beautiful coastline for future generations takes planning. The council's Proposed Regional Plan sets out rules and guidelines for the region's "coastal marine area", which is the area from mean high water springs to the 12 nautical mile (22.2km) limit of New Zealand's territorial sea.

The proposed plan sets rules regarding mangrove pruning and removal, which vary according to the size of the mangroves and where they are.

Go to the Proposed Regional Plan page

Where they grow

The mangrove trees of New Zealand only grow in the top half of the North Island of New Zealand. On the east coast they extend naturally as far south as Ohiwa Harbour in the Bay of Plenty, and on the west coast Raglan Harbour is generally regarded as their southern limit. Sometimes they are found in Aotea and Kawhia harbours a little further south.

Mangroves mostly grow in warmer climates, reaching their greatest size and diversity in the tropics.

There are 50 species in South-East Asia, with more than 30 in northern parts of Australia. However, in the southern parts of Australia and the northern part of New Zealand, where the climate is cooler, only one species of mangrove exists - although they have different names. In Australia it is called Avicennia marina while in New Zealand it is called Avicennia resinifera.

The word "mangrove'' refers to all types of trees that have adapted to living in the sea. Worldwide there are 23 genera from eight different families that have species described as mangroves.

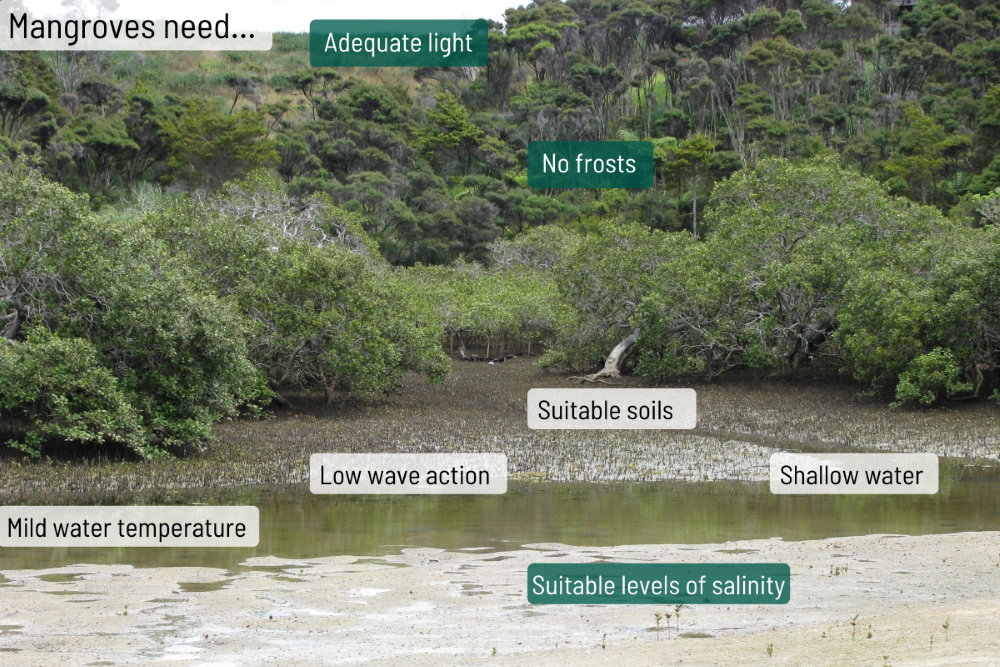

Needs

Mangroves need to grow in quiet waters such as inside harbours and estuaries, because exposed areas would either uproot them or carry away the silt in which they would take root.

They can tolerate being completely submerged in seawater but need to be uncovered for at least half of each tidal period so that the trees can absorb oxygen.

Mangroves hate frost, which is why they like the warm, Northland climate so much. The warmer the climate, the bigger they grow.

Adaptations

Too much salt

Mangroves stand in saltwater all the time, and this is the reason for some of the plant's greatest adaptations. They use a number of clever mechanisms to regulate the amount of salt in their sap, so they can survive in seawater.

Full strength seawater has a salt concentration of about 34 parts per thousand, or 34 grams per litre. The cell sap concentration of the New Zealand mangrove is about 2 grams per litre.

This is much higher than land plants which have sap concentrations of 0.2 grams per litre, but still much lower than seawater.

Mangrove leaves have several adaptations for salty living.

Mangrove leaves have several adaptations for salty living.

Mangroves can survive in such a salty environment because the salt water in its sap stops water loss from the plant tissues.

The leaves of the mangrove also help the plant regulate its salt content by being able to secrete salt. Under a microscope, hundreds of tiny pores can be seen on the upper surface of a mangrove leaf.

These are the openings of salt-secreting glands which get rid of extra salt by exuding a brine that is more concentrated than full strength seawater. Along with the salty residues of splash and spray, this is easily rinsed away by rain or the rising tide.

Another way of getting rid of salt is by shedding leaves. Many plants use this as a way of isolating and getting rid of unwanted chemicals in old leaves.

Mangroves lose about 60 percent of their leaves in a year. In summer, when the water loss through evaporation would be greatest, the mangrove increases its leaf drop by 10 times.

In the Far North, the annual litter drop is about five to six tonnes per hectare. Many of these leaves are trapped among the pneumatophores (aerial roots) and are quickly broken down by soil fungi and bacteria to make their nutrients available for reabsorption by the mangroves - but now with the salt leached out into the seawater.

Waxy leaves

Mangroves have developed a wetsuit to help them survive in seawater. The upper surface of mangrove leaves has a thick, waxy cuticle that makes the leaves waterproof. As the tide falls away, the salty water drains away quickly from the pointed tips of the leaves.

However, the waterproof covering cannot encase the leaves entirely because the leaves still need to breathe to allow photosynthesis to take place. Photosynthesis is a process all plants go through to transfer sunlight and gases, so they can stay healthy and grow.

In mangroves, the breathing pores (stomata), which allow carbon dioxide in the air to diffuse into the photosynthetic tissue inside, are tucked in sunken pits on the undersides of the leaves. This protects the plant from air currents that would carry away water vapour.

As an extra precaution, the underside of the leaves is coated with fine hairs that form an insulating blanket to reduce air flow.

A waxy coating helps mangroves survive.

A waxy coating helps mangroves survive.

Root system

The root system of a mangrove has two functions:

The root system of a mangrove has two functions:

• Anchor the tree firmly in the ground so it doesn't fall over; and

• Absorb water and dissolved nutrients in the soil for use by the plant.

Most other flowering trees only have to cope with wind, but the forests of the harbour also have to contend with water forces as tides rise and fall or when rivers are in flood after heavy rain.

The root system of the mangrove grows to spread much wider than trees that grow on the land.

The mangrove cannot send its roots deep into the fine estuary silt because this is packed so tightly that there is virtually no air, which the tree needs to survive.

Instead, the trees form extensive "root rafts'' radiating out from the trunk, often up to five times the diameter of the canopy. Trees on the land usually have root systems that match the diameter of the canopy. The roots of trees intertwine forming a mesh of support.

Snorkel city

Along each radiating root, mangroves send up thousands of snorkels above the mud. The mangrove's breathing roots are called pneumatophores, which means "breath carriers''. These serve as snorkels by carrying air down to the roots. Each has small "port holes'' (lenticles) in the outer surface which let air into the root when the tide is out.

Pneumatophores vary in thickness from 6mm to 12mm diameter, and in length depending on the conditions in which the tree is growing.

In open, sandy sites, where the soil is better aerated, pneumatophores might be only 5cm tall, but in deep, sloppy mud sites they might grow to be half a metre tall.

Ground stabilisers

The specialised root system acts as an obstacle, slowing the flow of the water and catching the silt particles floating in the water. Over time the root systems generally stabilise the surrounding soil so that other plants can take root.

Saltmarsh plants such as rushes and sedges will settle in first, followed by bush and hardy, salt-tolerant grasses. Eventually, this process can lead to natural land reclamation.

Flowers

Bees are attracted to the mangrove flower's sweet scent. A close-up of the golden flower is inset.

Bees are attracted to the mangrove flower's sweet scent. A close-up of the golden flower is inset.

Mangrove trees rely on insects to fertilise their flowers. The New Zealand mangrove's flowers are about 6mm in diameter, in clusters of four to a dozen blooms at the tips of branches. The four-pointed petals have a tough brown, hairy outer surface, but inside they are golden and shiny.

They entice insects with a scent of tropical fruit blended with sweet sherry. Insects attracted include the introduced European honey bee and the small native common blue butterfly, as well as several species of native bees and small flies.

Beekeepers often move their hives close to mangrove forests because the bees make a distinctively fruity flavoured honey from the nectar of the mangrove flowers.

The main flowering period extends over several months in later summer and autumn, although each individual flower is only fertile for three or four days.

Baby mangroves

Once the flower is fertilised, the mangrove uses another of its tricks for survival in the salty environment of the harbour.

It does not produce seeds as other trees do. The mangrove tree gives its young mangroves, called propagules, the best chance of survival by letting them develop in protective casings on the tree.

Conventional seeds would have a very low success rate in the wet mud, and the constant movement of the tide would not give the young mangroves enough time to take root.

When the propagules finally fall from the tree around Christmas time, they are all set to unfold and take root quickly in between tides if they find the right soil. However, just in case they don’t find the right spot immediately, the propagules have a portable food supply and life jacket to float to somewhere better on the next tide.

Air inside the leathery casing allows a propagule to float for up to three days. The case then splits to release the bright green propagule inside. If the naked propagule settles in a good spot at that stage, it may take root straight away.

However, if you walk along the high tide line of the Northland coastline, it is obvious not all are successful at first. But the propagules do get a second chance by becoming buoyant again after a few days of lying on the beach. Tests indicate that propagules remain viable for at least four months, perhaps longer.

Mangrove propagules fall from the tree after a few months, but may not always take root the first time. You might see them on the beach at high tide before they grow into tiny trees.

Growth rates

The growth rates of mangrove trees and the size and shapes they reach differ widely and depend on a lot of factors:

- Climate warmth

- Type of soil

- Salinity of the water

- Position on the shoreline

- Length of time standing in water; and

- Density of surrounding mangrove forest.

In the Far North, large trees up to nine metres tall are commonly found in harbours such as Whangaroa and Hokianga. Further south the height of trees gradually decreases.

In the Whangārei district, mangroves reach about five metres while they are about a metre shorter around Auckland.

A forest of mangrove trees acts as a breakwater to reduce coastal wave erosion.

Home sweet home

Algal scum floats among the mangroves.

Algal scum floats among the mangroves.

Algal growth is abundant in the warm waters of the mangrove estuary, and sometimes there is such an abundance of phytoplankton that the water has a greenish tinge.

The richness of the mangrove habitat makes it an ideal spot for fish, crabs, snails and crustaceans to set up home. These attract an abundance of sea birds eager for an easy meal.

The boundaries of some properties extend across harbour flats and property owners are encouraged to fence off these areas to protect the mangrove trees.

Importance to Māori

The Māori name for mangroves is manawa. Māori traditionally gathered food from among the mangrove forests. This included mullet (kanae), oyster (parore tio), sea snail (karahu) and eel (tuna).

Points of interest include:

- The black earth formed by rotted mangrove leaves was used to dye flaxes which were used for making kits and piupiu skirts

- A green dye was made from the lichen on mangrove trees

- Branches were sometimes fashioned into fern root pounders

- Mangrove leaves were sometimes used to keep fish cool on fishing trips; and

- Dry mangrove wood was not used for heating hangi stones because it gave out too much heat and burned with a pungent smell.

Under the boardwalk

A pleasant way to see mangroves is in a dinghy or kayak, where the tranquillity of the scenery can make the rest of the world seem like it’s miles away.

A pleasant way to see mangroves is in a dinghy or kayak, where the tranquillity of the scenery can make the rest of the world seem like it’s miles away.

Boardwalks have been constructed in several places in Northland, so mangroves can be studied at close quarters without getting your feet wet. Boardwalks protect the pneumatophores - the breathing roots - and radial root systems from being crushed. Among these are:

Whangārei

Two boardwalks meander through mature mangrove trees in the city. One is in the Town Basin area, just up the Hatea River from the swimming pool complex. Access is from the swimming pool carpark in Ewing Road.

The other is on the banks of Limeburner’s Creek and can be accessed from Kioreroa Rd.

Bay of Islands

There are two boardwalks in the Bay of Islands. The Waitangi mangrove walk, located between Haruru Falls and Waitangi, is accessed opposite the Treaty Grounds.

Another is between Opua and Paihia as part of the coastal walkway. The boardwalk is accessed near Smith's Holiday Camp, Paihia.

There is also a boardwalk at Rawene, accessed from Clendon Esplanade.

History

Mangroves in New Zealand caused confusion for the botanists on Captain Cook's first voyage. They would have seen mangroves before, because they grow in many other parts of the Pacific.

However, the botanists found large lumps of gum on the soft ground among the trees, and so named the trees Avicennia resinifera - which means ``the resin-bearing Avicennia''. They did not realise the gum had come from the kauri tree and had been washed down in flood waters.

Over the years, mangroves were regarded as having little value - they were even regarded as a weed by some people. Roads were formed around coastal shores, with causeways allowing too few channels to flush upper tidal areas properly. Silt built up quickly, smothering pneumatophores and killing trees.

Rubbish was often dumped legally and illegally around mangroves. Tip sites were still being permitted in mangrove forests in the late 1970s. Land reclamation was another major threat to mangroves. Large flat areas were created as cheap industrial land in many areas. However, this sometimes led to flooding problems, because mangroves and associated wetlands can act as a buffer zone to absorb stormwater in times of heavy rainfall.