Water quality

Despite our high rainfall compared with other parts of the country, clean water is one of Northland's most scarce resources. The small area of land means most rainfall drains quickly away to the sea. Most of the rivers we have are short and slow moving and they are often heavily influenced by ocean tides near the coast.

Common water uses

The average New Zealander uses between 250 and 300 litres of water per person per day. Some of these uses are outlined below.

- Cooking, drinking and hand washing - 25 litres per person.

- Bathing - 80 litres per person.

- Showers - 30 litres per person.

- Toilet - 3-9 litres per flush (dual flush).

- Automatic washing machine - 49-100 litres per wash (depending on efficiency of machine).

- Dishwasher - up to 35 litres per wash.

- Dripping tap - up to 3640 litres per year (that’s more than a bath-full each week).

- Hose or garden sprinkler - between 1000 and 2000 litres per hour.

Fresh water is often taken for granted. Remember to turn off the tap while brushing your teeth.

Fresh water is often taken for granted. Remember to turn off the tap while brushing your teeth.

Northland Regional Council's role and policies

Under the Resource Management Act 1991, the Northland Regional Council's key role is to promote the sustainable management of Northland's water resources.

This requires water to be available for people to provide for their wellbeing.

The provision of water needs to be done in such a way that it is not at the expense of future generations or its life-supporting capacity and it does not cause any significant harmful effects.

The regional council controls the taking, use, damming and diversion of water. It also controls activities and discharges that may affect the quality, level and flow of water in water bodies. Many of these activities need resource consent, and consideration is given to the council's regional plans and policies before applications are granted.

The Regional Water and Soil Plan for Northland identifies significant water and soil issues so that these resources can be sustainably managed. There are rules in the plan to cover all sorts of activities involving discharges, taking or use of water and land disturbance. Many activities with minor effects don't need a resource consent while others do or are prohibited.

The Regional River Water Quality Monitoring Network has been operating since 1996. The network provides information about river water quality in the Northland region so that baseline levels and water quality trends can be monitored.

What is water and why do we need it?

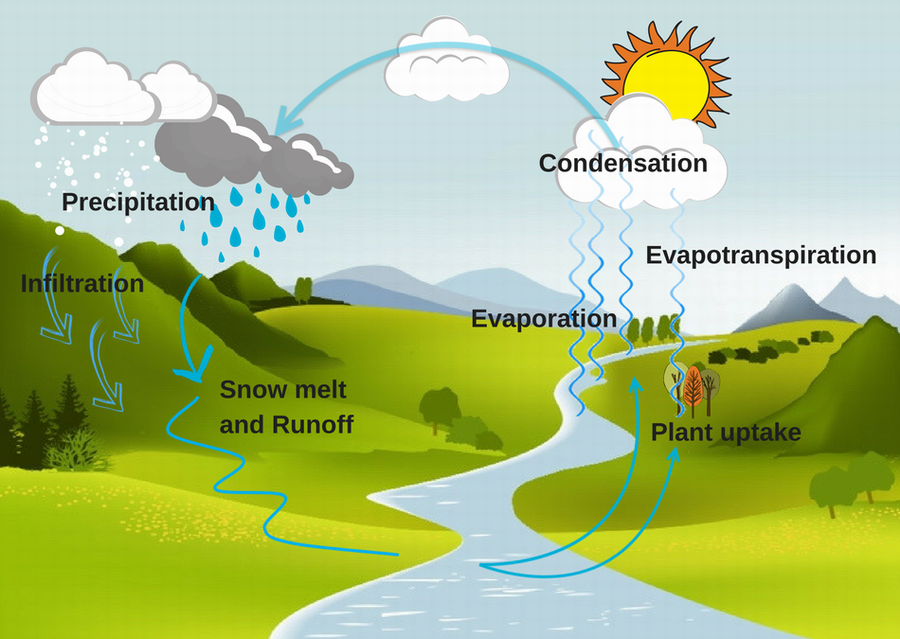

Water is needed by all living things to survive. It is a colourless, transparent, tasteless and odourless compound of oxygen and hydrogen in a liquid state. In fact, humans are composed of large amounts of water. Water continually circulates from the oceans to the atmosphere to the land and back to the oceans. This complex process is known as the water cycle. It keeps a balance between water in the oceans, water on the land and water in the atmosphere.

The water cycle

Fresh water resources

Northland's fresh water resources include rivers and streams, lakes, wetlands, springs, groundwater (aquifers) and dams. See Rivers and Streams information pack.

Fresh water is used in many ways:

Domestic: A large proportion of domestic water is drawn from groundwater and much of it is untreated.

Agriculture and horticulture: Farmers and orchardists need large amounts of water for irrigation, stock water supply and cowshed milking processes and cleaning.

Urban: Cities and towns use fresh water for drinking and sewage disposal. Most urban areas have piped water supplies, often fed from large dams. This untreated water undergoes a treatment process to make it safe for humans to drink.

Industrial and commercial use: Big factories such as meat works and processing plants need large quantities of water for day-to-day running.

Dams: These can range from small farm dams for stock water and irrigation to larger dams for large scale irrigation and recreation.

Recreation and tourism: Water-based adventure tourism such as white water rafting and eco tours are popular in many parts of New Zealand. Holidaymakers enjoy water skiing on fresh water lakes. Swimming, rafting, yachting, kayaking and windsurfing are among the many popular water activities in Northland.

Aquaculture: Fish farms are another use of fresh water.

Swimming is just one of the many popular water activities in Northland.

Swimming is just one of the many popular water activities in Northland.

Importance to Māori

In Māori culture, water is an essential ingredient, regarded as a taonga or treasure and it must be safeguarded for future generations. Water is considered to possess a life force, mauri, and have a spirit or wairua. Any discharge of contaminants into water, no matter how well purified in a treatment process, therefore reduces the water's ability to sustain life and reduces its mauri, or life force.

The Waitangi Tribunal provides guidance on the importance of water to Māori including five principles:

- Fresh water is a life-giving gift.

- The Māori conception of rivers is holistic.

- It is irrelevant to consider whether waste can be treated to be "pure" before discharge into rivers.

- Only Tāngata Whenua can determine the spiritual and cultural significance of a river resource to Māori.

- Environmental consultation with iwi is a council duty under the Resource Management Act.

It is important to Māori that water remains pure and uncontaminated in order to continue to protect, preserve and sustain life into the future. Wai is the Māori word for water, and many New Zealand places feature it as part of the place name, giving a clue to its meaning.

Water is given different terms by Māori according to its status.

Waiora is water in its purest form, usually rainwater caught before it touches the earth. This water is used for ritual purposes.

Wai Māori is fresh water or drinking water from springs. It can be used for everyday purposes.

Waimate or Waikura is water that is stagnant or polluted and is no longer capable of sustaining life.

Influences on water quality

A wide range of factors - many of which result from human activities - have an influence on water quality. There is a strong relationship between land use and the water quality of streams, rivers and groundwater. The greatest area of intensive land use is in the lowland area where the river gradient lessens and water movement slows down. Generally, Northland's lowland streams are highly affected by human land use practices and this is having a negative effect on water quality.

Erosion and sediment

Sediment can come from a number of sources such as eroding river banks, land slips and earthworks. Sediment suspended in waterways can be carried a long way downstream and even out to sea in storm events. Muddy water can impact aquatic organisms, affecting the ability of fish and other aquatic organisms to feed and breathe. When sediment becomes deposited on stream beds it can smother important habitat and breeding grounds and can encourage the growth of instream plants (macrophytes). Sediment particles can also carry nutrients and sometimes chemicals/metals into the water with them.

Sediment from a single road development leaves deposits on the stream bed as it flows out into the Whangarei Harbour.

Sediment from a single road development leaves deposits on the stream bed as it flows out into the Whangarei Harbour.

Forestry

Forestry is a major industry in Northland, with thousands of hectares being changed from farmland into forestry blocks. Trees are harvested every 25-35 years, which means for most of the time the trees are growing and there is little disturbance to the land. However this situation changes when trees are harvested and the next crop is planted. The harvesting/planting process can increase runoff and result in a lot of soil ending up in rivers and streams. This is why forestry operators must leave a riparian barrier to help filter sediment and keep it out of waterways during this time. Sediment traps are also used to prevent soil getting into the waterway. Forestry can also use a lot of water affecting nearby surface and ground water levels.

Farming

Another major industry in Northland is farming, which can have a significant effect on water quality in streams, rivers and groundwater. When cows have access to waterways they cause pollution when they defecate in water and their movement causes stream bank erosion. When it rains faecal contaminants are also carried as run-off into rivers and streams and groundwater. While improvements have been made, farming practices still affect water quality through run-off from chemicals and fertilisers, dairy shed effluent, silage pits, farm races and reliance on streams and rivers for stock drinking water. Fonterra is working with dairy farmers and now operates under the Sustainable Dairying: Water Accord. This requires that stock on dairy farms is excluded from waterways. Stock exclusion across the board is likely to become mandatory in Northland by 2025.

Fencing stock from waterways helps to prevent pollution and stream bank erosion.

Fencing stock from waterways helps to prevent pollution and stream bank erosion.

Horticulture

Growing crops and trees can negatively affect water quality through the use of fertilisers, pesticides and herbicides. These nutrients and chemicals can end up in the soil and run-off, which in turn can end up in groundwater and streams. Horticulturists are encouraged to use as few chemicals as possible and organic farming is gaining in popularity as people consider how to reduce contamination of land and water.

Urban development

High concentrations of people in cities, towns and other settlements have a significant effect on water quality. Domestic or sanitary wastewater is treated in sewage treatment plants. It comes from residential sources including toilets, sinks, bathing, and laundry. It can contain body wastes containing intestinal disease organisms as well as other nasties such as phosphates from laundry detergents.

In built-up areas, kerbing and stormwater outlets collect water that runs along streets, down the drains and into the rivers and sea. Everything that is thrown on the roadside can end up in the stormwater system and be washed into streams, negatively affecting water quality. Contaminates can also filter through the ground into groundwater.

Paint that is tipped down drains ends up in our waterways.

Paint that is tipped down drains ends up in our waterways.

Cars and trucks on the road or parked in car parks can drip oil and fuel. When it rains these oil drips are washed into the stormwater drains. People cleaning their cars often allow the suds from their detergent to flow into the drains. Some people even throw left-over paint or engine oil down drains without thinking about how this poisonous brew will end up in our waterways.

Wrappers from fast food outlets are one of the major sources of litter in city streets, which can be carried with the rain into drains. While each single incident may seem a small amount of waste, the combined effects of such actions are significant. We all need to remember: "Drains should only drain rain.''

Have a look around your city, town or roadside. See what you can find waiting to pollute waterways.

Have a look around your city, town or roadside. See what you can find waiting to pollute waterways.

Industrial Development

Factories and businesses produce different types of waste as by-products of their processing. These discharges include treated industrial waste water that can contain rinse waters containing residual acids, plating metals, and toxic chemicals and fumes. These can rise up into the atmosphere causing pollution that is then brought down to earth when it rains, affecting water quality in rivers and the sea. Trace metals as by-products of manufacturing processes can also enter water bodies as run-off from rain, while dust and fertiliser particles can affect water quality near fertiliser works. The Northland Regional Council keeps a check on factories and businesses and encourages them to consider how they can reduce waste at all stages of their production processes – right through from creation to disposal of their products once they have reached the end of their useful lives. The council also sets and monitors resource consent conditions to make sure that industrial processes meet the standards set and have minimal adverse effects on the environment.

Geology and soils

Geology can have a significant effect on water because the rock a river flows through influences the mineral content of the water.

The speed at which the water flows also affects water quality. Fast-moving water tends to stay cooler and can have higher levels of dissolved oxygen due to the turbulence of crashing over rocks and water falls. Slow-moving water tends to be warmer and warmer water carries less oxygen then colder water. Increased temperatures can also increase algal growth.

Fast flowing water washing down from the Wairere Falls.

Fast flowing water washing down from the Wairere Falls.

Trampers in native bush

Water flowing through native bush usually looks pure, inviting and good enough to drink - but appearances can be deceiving. The natural decomposition of leaves dropped from trees affects water quality, and micro-organisms in the water can be a danger to both people and animals. More and more trampers are walking our bush tracks and leaving their mark on water quality by accidentally introducing bugs to waterways. These include giardia, which can leave people ill for months with stomach pains and diarrhoea. It is now thought that possums have picked up these bugs and have spread them throughout our waterways. This is why water from streams should always be boiled for at least 10 minutes to kill germs that might make you sick, even if the water looks pristine.

Physical issues

Water quality is affected by physical issues such as temperature, the amount of dissolved oxygen and the amount of vegetation shading waterways. The shade from trees helps reduce water temperature by restricting the amount of sunlight reaching it. This in turn reduces the amount of algae, which need sunlight, warmth and nutrients to be able to grow. Riparian strips are areas of vegetation alongside waterways. As well as providing shade, they need to be wide enough to help filter and reduce the amount of run-off from pastures.

Rivers and streams

Northland has a dense network of rivers and streams, although none of them is considered major on a national scale. Northland's narrow land mass means most of our rivers are relatively short with quite small catchments. Most of the major rivers have their outlets into harbours, with only a few discharging directly to the open sea. The Northern Wairoa River is Northland's largest river, draining a catchment area of 3650 square kilometres, or 29 percent of Northland's land area. The Northern Wairoa is tidal for about 100 km. See the Rivers and Streams Information Pack for more information about rivers and streams in Northland.

Lakes

Northland has a large number of small, shallow lakes and associated wetlands. Most of these have been formed between stabilised sand dunes on the west coast. These dune lakes are grouped on the Aupouri, Karikari and Pouto peninsulas. Most are between five and 35 hectares in area and are generally less than 15 metres deep. Lake Taharoa of the Kai Iwi group near Dargaville is one of the largest and deepest dune lakes in New Zealand. It covers an area of 197 hectares and is 37 metres deep.

Find out more about Northland's lakes and why they're so special at:

www.nrc.govt.nz/hiddengems

Lakes are different from rivers in that they may have little or no outlet so any contaminants tend to stay in the water body for a lot longer. A lake is more susceptible to heating by the sun and the warmth encourages plant growth, making weed overgrowth and algal blooms more likely. Some algal blooms can be toxic to animals and humans – such as a significant bloom in Northland's largest lake, Lake Omapere in 1985.

Grass carp have since been introduced to eat oxygen weed in the lake and reduce the chance of another toxic algal bloom. The council and the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) are continuing to monitor the lake’s water quality as it slowly continues to improve.

Lake Taharoa is one of the Kai Iwi dune lakes. Dune lakes are one of the rarest and most threatened aquatic habitats in the world.

Lake Taharoa is one of the Kai Iwi dune lakes. Dune lakes are one of the rarest and most threatened aquatic habitats in the world.

Groundwater

Groundwater is water under the ground, which collects in water bodies called aquifers. Aquifers are filled by water that is filtered through soil and rock. Many of them are used as water sources by land owners who have bores and wells. Groundwater can be contaminated in a number of ways: by leaks from septic tanks, underground fuel tanks and pipes, landfills, mines, timber treatment leachate, chemical spills, offal holes, pesticides and fertilisers.

Salt water can contaminate aquifers if excess water is drawn from coastal bores. When the fresh water level in the aquifer falls too far, the salt water can seep in to replace it.

The area around the top of a well needs to be sealed properly so that aquifers are not contaminated through the hole or down the side of pipes. Chemicals should not be stored or sprayed near the well opening. Animals should not be able to fall down it and surface water should not be able to drain into the well. The well hole should never be used as a dumping ground, even when it is no longer in use, because of risk of contaminating the underground water supply. Underground water should not be allowed to bubble up from the ground through unsealed bores because of the waste of water, drop in underground pressure and risk of contamination. Groundwater contamination affects human and animal health, as well as impacting on crops and aquatic ecosystems. See the Rivers and Streams information pack.

Checking it out

There are many indicators of water quality and they help us determine the overall health of a waterway. Clues to look for include water clarity and colour, temperature, instream plants and algae. Certain types of macroinvertebrates and fish have a low tolerance of pollution and their presence in good numbers can indicate a healthy stream.

Chemical monitoring can help build a picture of what is happening in a waterway.

Chemical monitoring can help build a picture of what is happening in a waterway.

Chemical factors

The pH scale: The pH scale (0 to 14) is used to measure the acidity or alkalinity of water. On the scale, 0 is very strong acid, and 14 is very strong alkaline. Pure water is neutral, scoring 7. Organisms in Northland streams are generally comfortable living with pH readings between 6.5 and 9. Beyond that they will move away or die.

Dissolved oxygen: Oxygen is important in water because fish and other aquatic life use it to breathe. Water naturally contains some dissolved oxygen and the amount varies depending on the temperature of the water. Waterfalls and rapids help aerate the water and this boosts dissolved oxygen levels. Conversely, bacteria use dissolved oxygen to break-down organic matter, such as sewage or rotting vegetation, and this can deplete oxygen levels to such an extent that aquatic life cannot survive. Along with testing dissolved oxygen levels, other chemical tests are conducted for conductivity, temperature, faecal coliforms, enterococci, total phosphorous, dissolved reactive phosphorous, nitrite and nitrate nitrogen, ammoniacal nitrogen, nutrient status, turbidity and water clarity.

Temperature: Temperature has a number of influences on water quality. Warmer waters tend to be more productive and are more likely to have algal blooms or blooms of aquatic plants. Biological oxygen demand tends to be higher in warmer waters often with wide fluctuations in oxygen levels between night and day. Warmer temperatures can stress aquatic organisms and particularly fish. Riparian planting can help by shading the water to keep temperatures down.

Nitrogen: Nitrogen is naturally found in a number of different forms in water but at high levels can be detrimental to water quality. Sources of high nitrogen include things like fertiliser run-off and discharges of organic or industrial wastes and sewage effluent. When nitrogen levels become too high it can cause algal blooms and too much growth of aquatic weeds. When these plants die, they are decayed by oxygen demanding bacteria, which may remove oxygen from the water and reduce the variety of invertebrate species, or in severe cases, kill fish.

Phosphorous: Phosphorus is an essential element for life; it is a plant nutrient needed for growth. In most waters, phosphorus limits growth because it is present in very low concentrations. This is because it is attracted to organic matter and soil particles. Algae and larger aquatic plants rapidly take up any remaining free phosphorus in the form of inorganic phosphates. Phosphorous levels can be elevated by stream erosion, sewage effluent, detergents, urban stormwater and rural run-off containing fertilisers and animal and plant material. When phosphorus levels exceed what is needed for normal plant growth the nutrient-rich water stimulates plant growth, resulting in problems such as algal blooms and growths. When plants and algae cells die, oxygen is used in the decay and fish are often killed.

Living Organisms: By observing the numbers and species of micro-organisms (organisms that can only be seen with a microscope) in a water sample, an impression can be gained of the water quality. These organisms use the nutrients in the water as a food source and can multiply rapidly. Large numbers can have a detrimental effect on the quality of a harbour, lake or river.

Algae: Algae are tiny plants. They are chlorophyll-bearing and can comprise one cell or many cells. Some float in the water while others attach themselves to rocks or other formations underwater. Algae present in large numbers can create an algal bloom which can sometimes be poisonous to people and animals.

Green filamentous algae in the Waitangi River.

Green filamentous algae in the Waitangi River.

Protozoa: These include flagellates, ciliates, amoeba and sporozoa (parasites). Some feed on algae, some on bacteria and some live on other protozoans. Many form cysts and can be airborne and dispersed when a water body dries up. An example of a protozoa is a malarial parasite called plasmodium.

Macroinvertebrates: Macroinvertebrates are small animals without backbones. They live in aquatic environments and include things like snails, worms and a wide variety of insect larvae which live on and under submerged logs, rocks, and aquatic plants on the beds of rivers and streams during some part of their life cycle. Macroinvertebrates play a central role in stream ecosystems by feeding on periphyton (algae), macrophytes (aquatic plants), dead leaves and wood, or on each other. In turn, they are an important food source for fish and birds. They are good indicators of water quality because of their different tolerances to pollution. Snails and worms tend to be very tolerant of poor water quality whereas others, such as stoneflies, are very sensitive to pollution. The type of macroinvertebrates living in a stream can therefore provide a good indication of water quality.

Mayfly larvae - Nesameletus.

Mayfly larvae - Nesameletus.

Emergency management

Northland is subject to a variety of hazards, which affect people, property and the environment. Flooding is the most common hazard - several of the region's major settlements, as well as important farming areas, are located within flood plains. Other emergencies could include pollution, such as when a milk tanker crashes and spills its load, or a factory that accidentally discharges chemicals into a stream. In such cases, the council would use monitoring equipment to measure the possible effect on the surrounding environment, or find the source of an unknown discharge point. The council keeps a constant check on water levels around Northland through data gathered at a number of water monitoring stations, many of which are on rivers. While flooding has a sudden and major effect on water quality, especially when there is a lot of sediment washed into streams and rivers, nature can usually recover quite quickly from these natural events.

Monitoring waterways to measure possible effects on the environment after spills or accidents is part of our role. Fortunately there was no threat to the nearby river after this tanker carrying sulpuric acid rolled on a Northland road spilling some of the contents.

Monitoring waterways to measure possible effects on the environment after spills or accidents is part of our role. Fortunately there was no threat to the nearby river after this tanker carrying sulpuric acid rolled on a Northland road spilling some of the contents.

What can you do?

Stream Monitoring with SHMAK kits: The New Zealand Stream Health Monitoring and Assessment Kit (SHMAK for short) is a tool that can help the general public measure stream health. The kit has been designed to be simple to use and measures important factors of a stream health, such as the temperature, velocity, pH levels and organisms living in the stream. Regular monitoring allows us to build up a record, and the information can be plotted on a graph to give an impression of how stream health is changing over time. The kits contain a manual with monitoring forms, full instructions and background information. There are coloured identification guides for bugs and slime, and a set of monitoring equipment including a water clarity measuring tube, conductivity meter, pH papers, thermometer, sample container and magnifier. The kits have been developed by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) in partnership with Federated Farmers of New Zealand. They are being promoted for use by the New Zealand Landcare Trust and are available to buy from NIWA Instrument Systems, PO Box 8602, Christchurch. More information is available on the NIWA website: www.niwa.co.nz

Checking stream health using a SHMAK Kit.

Checking stream health using a SHMAK Kit.

Streamcare groups: Adopt a stream near your school and undertake water monitoring. Remove any litter, and find out what types of industry upstream may be affecting the water quality. Support tree planting efforts, and discourage any of your friends or family from littering or pouring anything down stormwater drains.

Save water

There are many ways we can save water. Here are some helpful suggestions:

- Adopt a tap in your household and make sure it is never left dripping.

- Turn off the tap while brushing your teeth.

- Repair dripping taps or leaking pipes straight away.

- Consider low-flush toilet options to save water.

- Wait until your dishwasher is full before using it.

- Clean drives and paths with a broom instead of a hose.

- Water the garden at cooler times of the day to reduce evaporation – a soaking every few days is better than a quick sprinkle every day.

- Use mulch to retain moisture.

- Collect rainwater from the roof to water the garden.

- Look for the AAA water conservation rating when buying new appliances.

- Have a shower instead of a bath.

- Put the plug in the sink when you wash your hands.

When hunting, fishing, tramping or boating:

- Keep soap, detergent and toothpaste out of streams and lakes. Use a bowl or cup.

- Fillet fish away from the water's edge

- Use toilets provided, or dig a shallow pit at least 10 metres from the river or stream.

- Wash and dry all equipment before and/or after entering waterways to prevent spreading unwanted pest plants and fish.

Find out about the Check, Clean, Dry programme at www.nrc.govt.nz/checkcleandry

Sources:

NRC staff; Well water pamphlet, Canterbury Regional Council; A Microscopic View on Water Quality; Water The Essence of Life pamphlet, Whangārei District Council; Stream Monitoring with SHMAK pamphlet, Federated Farmers and NZ Landcare Trust; Fresh Waters of Canterbury pamphlet, Canterbury Regional Council; Lake Omapere submission, Rio+10 Community Programme information pack.